Why Landmines Still Matter in Global Security Debates

Landmines—albeit a particularly explosive topic (sorry, I had to)—feels like a litmus test for Beyond Agreement. While our usual discussions revolve around polarizing issues with passionate arguments on both sides, I’m genuinely uncertain whether this one will spark much disagreement. We’ve seen this movie before. We know the catastrophic injury, unintended death, and long-term devastation landmines cause.

Even if this topic doesn’t stir much disagreement, I hope it stirs a sense of activism in you. We need to let policymakers and leaders know that this reversion is not the world we want to live in. However, please also know—as always—I am an active listener and truly wish to hear from you on your varying perspectives on this matter.

The Ottawa Treaty and the Global Anti-Landmine Movement

Recently, I came across a jarring article by Daniel Otis at CTV News: “Ukraine and Five Other Countries Leaving Canada-led Treaty that Banned Landmines.” Otis speaks about the Ottawa Treaty, a pivotal agreement in international law signed by 122 countries in 1997, all agreeing to “prohibit the use, stockpiling, transfer, and production of anti-personnel landmines.”1 But what’s key in Otis’ article is that this humanitarian initiative is backsliding, and there will be severe, decades-long fallout as a result.

Princess Diana, Bosnia, and the Power of Humanitarian Advocacy

Otis’ headline transported me back to the late 1990s, when, as an 11-year-old, the global anti-landmine movement broke through to my young world with unexpected force. My most vivid association from that era was Princess Diana, whose advocacy for landmine victims and her visit to war-torn Bosnia became iconic symbols of humanitarian activism.

Even as a child, I remember the powerful messaging: landmines are indiscriminate killers. They maim and kill long after the fighting ends. The global response felt like a collective awakening—a moral reckoning that these weapons had no place in modern warfare. I recall countless commercials—raw, emotional appeals featuring real survivors and devastated communities—broadcast across Western media, urging donations to support demining efforts, civilian protection, and post-conflict recovery. These weren’t abstract policy debates; they were visceral glimpses into lived experience, and they made the issue impossible to ignore.

The Dangerous Reversal of Landmine Policy

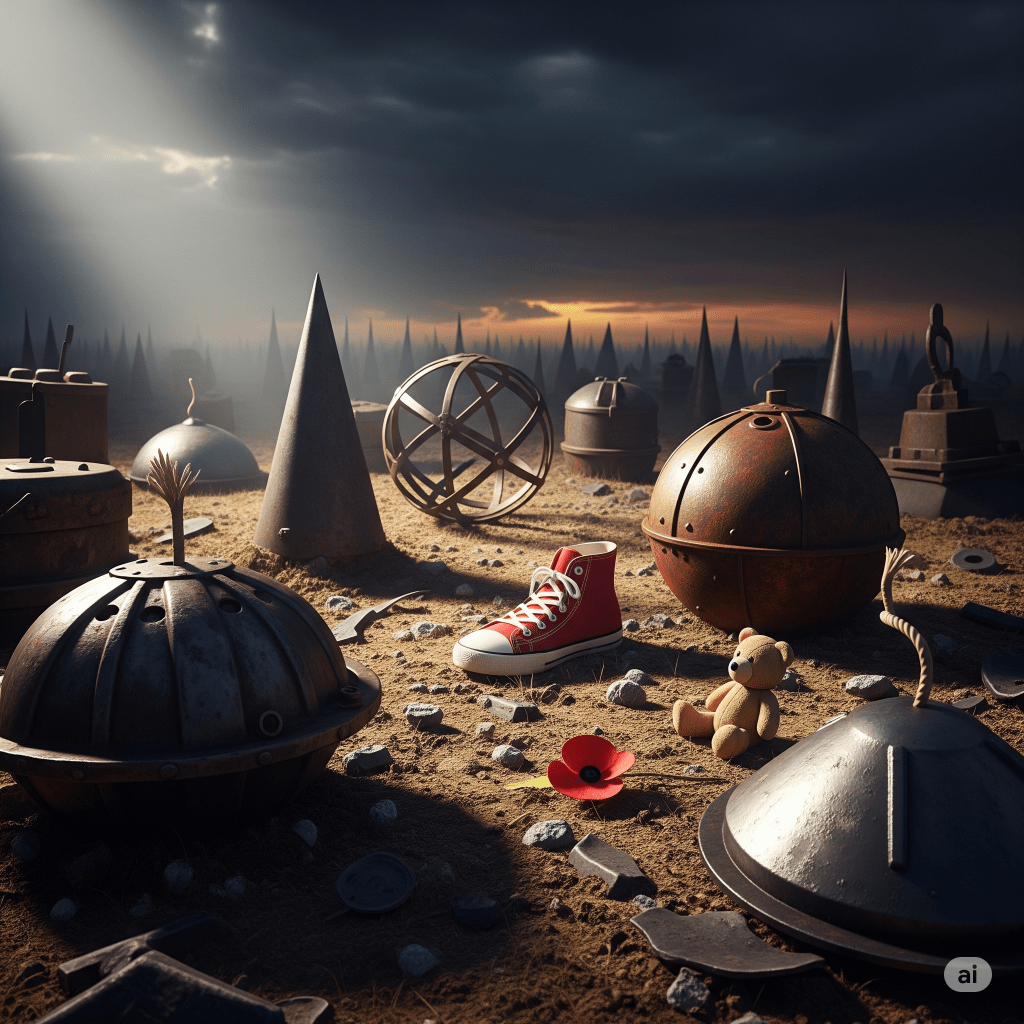

So to witness a retreat from that consensus today feels especially counterproductive. It’s not just frustrating—it’s draconian. Landmines are a relic of a darker age, and their resurgence signals a dangerous regression in military ethics.

The damage of war doesn’t end when the fighting stops. Landmines linger—silent, hidden, waiting, still claiming lives when no one’s looking. They are a legacy not just of war, but of a profound failure to consider the future.

Modern Warfare vs. Outdated Weapons: A Stark Contrast

And here’s the paradox: we live in an era of cutting-edge military technology—AI-driven systems, precision-guided weapons, and advanced demining robotics. So why, in this age of advancement, are we regressing to crude, barbaric tools straight out of the early 20th century? History may repeat itself, but perhaps Einstein’s definition of insanity applies here: repeating the same behavior and expecting different results. To return to landmines is to embrace a cycle of destruction we already know ends in civilian casualties, displacement, and human suffering.

The Ottawa Treaty’s Unraveling in the Wake of the Ukraine War

The Ottawa Treaty, signed in 1997 and enacted by 1999, was a pivotal moment in global security policy. Over 80% of the world’s countries agreed to prohibit the “use, stockpiling, transfer, and production of anti-personnel landmines”1. Notably, major powers like the United States, Russia, and China did not sign. However, President Clinton pledged to uphold 90% of the treaty’s targets and committed resources to global demining programs.1

Fast forward to today: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has upended the treaty’s trajectory. As a non-signatory, Russia has deployed landmines throughout its campaign. In response, the United States reversed its previous stance in 2024, transferring landmines to Ukraine for defense—abandoning Clinton’s earlier commitment.2

Then came the domino effect. In March 2025, Ukraine, Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and later Finland, declared their intent to withdraw from the treaty, formalizing their exit on July 1, 2025.2

Geopolitical Strategy vs. Humanitarian Responsibility

It’s worth noting that some nations originally signed the treaty not solely out of ethical conviction, but as a gesture of alignment with NATO and EU values—a strategic move to gain entry into Western alliances, as Keir Giles noted in Al Jazeera.2

And I do empathize with these nations. How can Ukraine be expected to defend itself against Russia without matching its firepower? The same goes for the Baltic states, bracing for potential invasion. It’s understandable that they would use every tool available to protect their borders.

But it’s a travesty that because some nations refuse to play by globally accepted rules of engagement, the rest of the world is dragged backward—toward draconian measures we thought we had left behind.

We must break free from decisions that burden generations to come. Our legacy should be one fit to live in, not rubble from which our children must claw their way out.

References:

Leave a comment